The Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī in Mughal India

Khwāja Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (d.672/1274) hardly needs any introduction. An influential political figure during the early Ilkhanid period, Naṣīr al-Dīn was a philosopher in the medieval sense of the word, which included not only philosophy per se, but also almost all ‘rational sciences’ (ʿulūm (sing. ʿilm) ʿaqlī or maʿqūl), such as astrology, architecture and medicine. He also was a leading theologian and wrote numerous works on different religious and scientific subjects in both Arabic and Persian. Apart from his astrological accomplishments in the Marāgha Observatory (built and run by himself), Naṣīr al-Dīn is often remembered as the reviver of Avicenna with the Arabic Sharḥ al-Ishārāt, a commentary on Avicenna’s al-Ishārāt wa’l-Tanbīhāt.

His most-famous Persian work, the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī, could also be regarded as an introduction to ‘practical morality’ (ḥikmat-i ʿamalī) to the Persianate audience. It is based on the Tahdhīb al-Akhlāq by Ibn Miskawayh al-Rāzī (d.1030), and is even a translation of the latter in the first part of the work, but Naṣīr al-Dīn adds a lot to the next two parts of his work which are about ‘domestic management’ (tadbīr-i manzil) and ‘politics of states’ (siyāsat-i mudun). Here he especially reminds the reader of al-Fārābī’s Ārāʾ Ahl al-Madīna al-Fāḍila (Opinions of the Citizens of the Perfect State).

Numerous copies of the work exist all around the world, and later works inspired by the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī underline its reception and high influence throughout the Persianate world. The Akhlāq-i Nāsirī was a useful collection of advice about morality as well as pragmatic domestic and civil policy, but it was also a work of philosophy, hence not easily digestible, especially since the big majority of the discipline terminology is in Arabic, despite the book being a ‘Persian’ work. Non-specialist audience without a firm grip on Arabic would have a hard time understanding what Naṣīr al-Dīn actually meant.

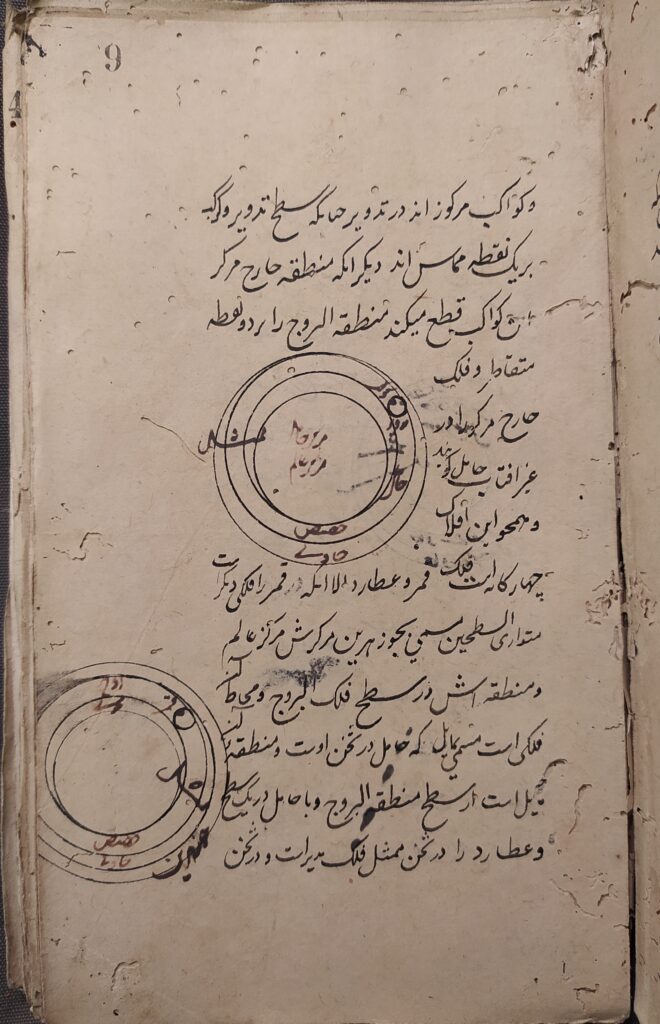

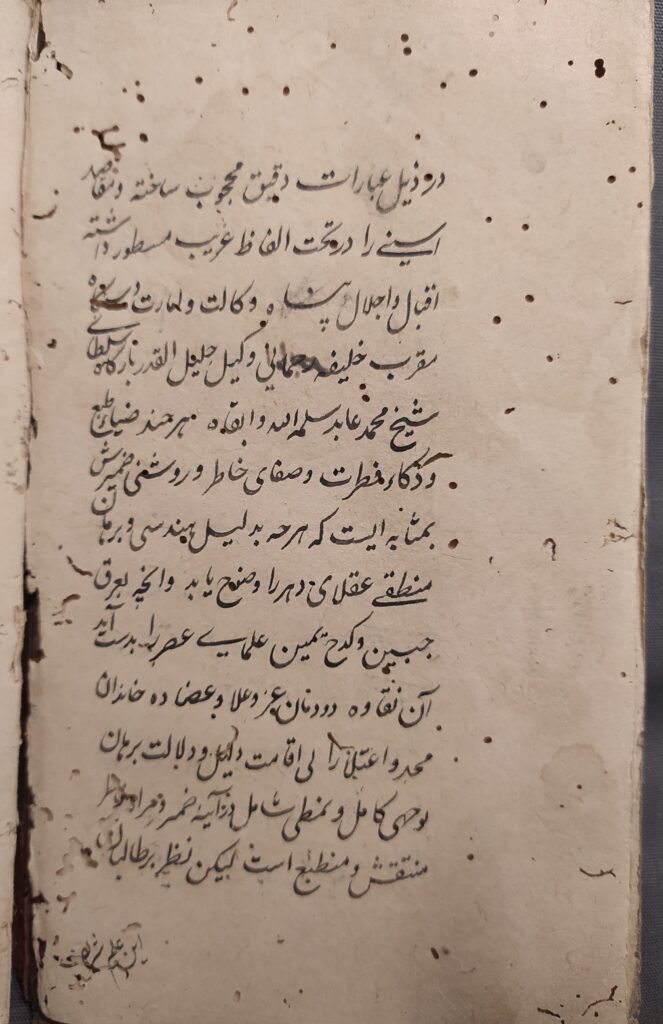

Indian consumers dealt with the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī in different levels. One example is British Library MS Delhi Persian 915-a, an autograph by a certain Luṭfullāh, son of (valad-i) Ustād Aḥmad Miʿmār Shāhjahānī. It was commissioned by one Shaykh Muḥammad ʿĀbid, who was apparently a vakīl related to a court. Lutfullāh states that despite being extremely useful, the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī has disguised its meanings under ‘minute phrases’ (ʿibārāt-i daqīq) and unfamiliar words (alfāẓ-i gharīb). Thus, although the patron himself did not need it, he commissioned the work to benefit the students who were keen to learn this science. This unnamed work has a more philosophical approach. Luṭfullāh assumes his audience knows Arabic, since he repeatedly quotes Arabic sentences and clauses and only explains their ideas, rarely engaging with the syntax and grammar, let alone lexicon. The author – whose architecture-related background suggests familiarity with geometry and mathematics – is keen to explain astrology and geometry behind some terms used by Naṣīr al-Dīn.

DP 915 is a composite volume, containing two works. DP 915-b is a collection of what could be called ‘useful points’, including historical, geographical and administrative information related to India, but also different sorts of data about fortune telling, and omens. Their relationship to astrology might explain how these two works ended in one codex.

Another composite codex is Delhi Persian 902B. It consists of two manuscripts; 902B-a is Miftāh al-Akhlāq, a commentary on the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī composed by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān bin ʿAbd al-Karīm ʿAbbāsī Burhānpūrī in 1085/1674-5, the 19th year of Aurangzeb’s reign. According to Burhānpūrī, after years of desiring a trustworthy copy of the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī, he had found a copy ‘ornamented by the handwriting of the composer and taught and reviewed by him again and again’. One can interpret ‘being ornamented by his handwriting’ as ‘being written by Naṣīr al-Dīn’ or ‘having notes written by him’. But in any case, Burhānpūrī states he had copied that manuscript and had reviewed it with expert ‘almost 14 times’, during which he wrote a lot of commentaries and explanations, which he compiled in his work.

The Miftāḥ al-Akhlāq has two sections. First comes an alphabetical dictionary often giving only meanings but sometimes connotations and explanations. With a few exceptions, all entries are Arabic. The second part is what Burhānpūrī promises to be the ‘translation and interpretation’ of the Quranic verses and the hadith in the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī, but rarely has anything more than mere meanings of the words and sometimes anecdotal Sufi information about people. Despite the confident introduction and promises, and unlike Luṭfullāh’s commentary, the Miftāḥ al-Akhlāq does not manifest any special familiarity with the subjects and the discipline in which Naṣīr al-Dīn wrote. Burhānpūrī’s work should be considered a companion for beginners, written by a seminary teacher who could only help his readers surpass the language barrier.

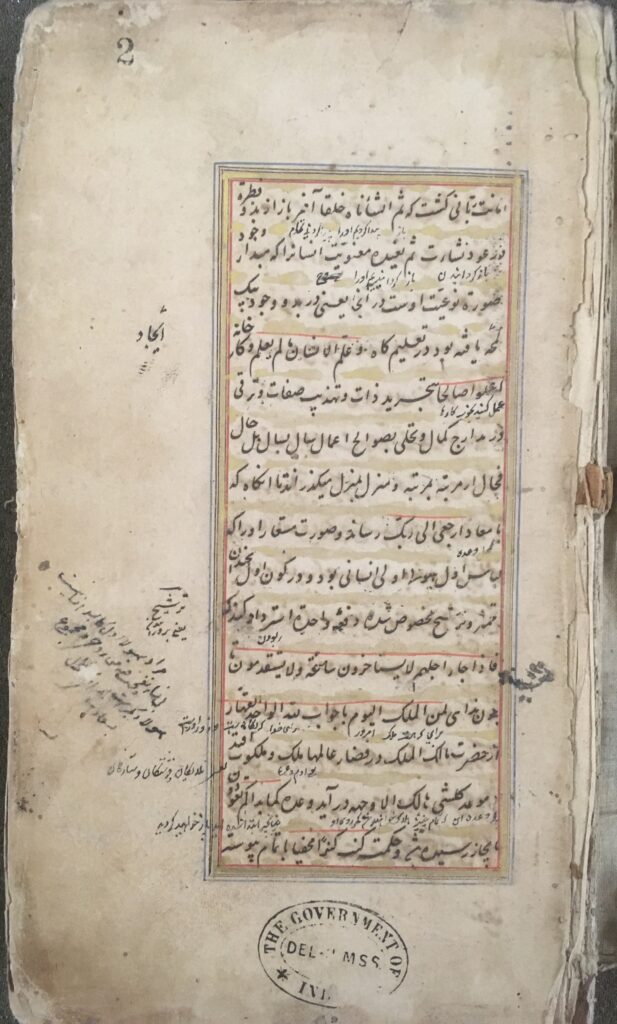

Delhi Persian 902B-b which comes after the Miftāh al-Akhlāq is a copy of the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī. An owner filled this copy with marginal and interlinear notes, which are translations of the Arabic phrases, clauses and sentences. 902A is another Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī, presumably from the 17th century. All the Arabic sentences in this copy have also been translated throughout. The translations are not the same in these two copies, so the translators did not use a handbook or commentary as their source but did apparently translate the sentences themselves. It is noteworthy that these translations do not try to use Persian equivalents for all Arabic nouns and adjectives. Rather, they use a lot of Arabic words, sometimes repeating the exact words in the Arabic text. So, the endeavours should be seen as a translation, probable with the aim to master Arabic syntax and verbs.

Apparently, the Akhlāq-i Nāṣirī had become famous/notorious for its difficult text, full of unfamiliar ‘Arabic’. Although this meant peculiar Arabic words in the Persian texts, Indian audience used it to practice Arabic. The linguistic distinction seems to be more important in Indian copies compared to those produced in Iran. In a lot of Indian copies written in Nastaʿlīq, Arabic sentences and clauses were written in Naskh. In other cases, they were written in colour (mostly red). Both these are also seen in Iranian transcriptions, but less frequently. On the other hand, in Iranian copies the distinction between secular and sacred texts (Quranic verses and hadith) seems more important. This observation could be tested with further studies.